Structured Mentorship

How we use Individual Development Plans to guide mentee growth

Most mentees are transient members of our research group. Their sun rises when they’re hired and sets when they graduate or otherwise move on to another position. While they are here, we want them to shine and leave their legacy through the work they do with us. By contributing to our projects, they’ll become part of our history while simultaneously developing their own unique scientific voice. My primary role as their research advisor is to understand their vision for their time with us—and for the larger arc of their career—and help them make that vision a reality.

A challenge in mentoring is that everyone arrives at our doorstep with a different background. Their scientific and life experiences are diverse and have led them to our group through uncountable independent paths. We’ve got to meet them where they are in their life, identify their vision for their time with us, and start walking toward that vision alongside them. Because each mentee is unique, there is no one magic set of mentorship rules that works for everyone—it is a highly individualized process, as no two scientists are alike.

To accommodate these differences, we’ve adopted Individual Development Plans (IDPs) as a tool to guide advisee growth and development during their time with us. IDPs are a structured way to frame a discussion about skills and skill gaps, professional goals (with timelines), and to build a mutually beneficial mentor-mentee relationship. IDPs are not designed to provide feedback on immediate experiments or near-term plans (we discuss these regularly). Instead, we focus on setting the trajectory for a trainee’s career in 6-to-12-month time blocks. This allows both the mentee and the mentor to take a step back from the day-to-day technical minutiae and ask bigger picture questions that allow us to observe large-scale progress toward the mentee’s vision.

The structured format of the IDP approach has several benefits. First, the goal of IDPs is not to treat everyone the same, but to look at each trainee as an individual. So, while the IDP process itself is structured the same for everyone, the content of the discussions and the feedback varies greatly from person to person. Second, we have a clear structure for our IDPs (described below), so it’s predictable. This predictability eases the inevitable mentee anxiety that comes with review-like processes. Finally, IDPs allow for a ‘bird’s eye view’ of the mentee’s professional development because of the relatively large time increments between them. This allows both the mentor and the mentee to observe incremental growth. Often, it’s so easy to get caught up in the immediate issues of a project that it’s hard to see (or remember) the degree of professional growth that has taken place over longer time periods.

Our IDP process.

Twice a year, I’ll post a message on Basecamp (see my video on how we use Basecamp to mange our lab) stating that it’s time to schedule IDPs along with an attached blank IDP form. The IDP form has gone through a slow evolution for our lab group but is generally based on this document from Lab Dynamics. Our current IDP form (without performance review section) is found here.

The mentee and I schedule a two-hour “IDP meeting” set for about 2 weeks after the announcement. This meeting is when we’ll discuss the completed IDP. In the time between the announcement and the IDP meeting, the mentee fills out their sections in the IDP form and returns the filled form to me. I review the mostly completed IDP and offer detailed feedback, and return to the mentee about a day ahead of the meeting (so there are no surprises).

The directions on the form are fairly self-explanatory. I encourage mentees to put significant time into filling the IDP form. The more detailed the responses, the better my feedback. In my experience, the most useful mentee feedback conveys their feelings and thoughts around lab work, our relationship, and their career. Even if some of the mentee’s thoughts are not fully fleshed out, by putting it in the IDP we can have a conversation around successes, anxieties, communication, or any number of other things that might be affecting the ability of the mentee to attain their vision. When providing written feedback, I try to be clear and straightforward, but detailed. Because no two mentees are the same, the feedback is varied. But in all cases, I anchor feedback in the context of their own vision for their time with us. At the end of the IDP there is a spot for three large picture items for the mentee to work on. I encourage students to write these down somewhere where they see them daily. Some examples of these big-picture ideas include developing small habits that have large impact over time, like learning to manage time effectively, developing a paper reading habit, or developing a writing habit.

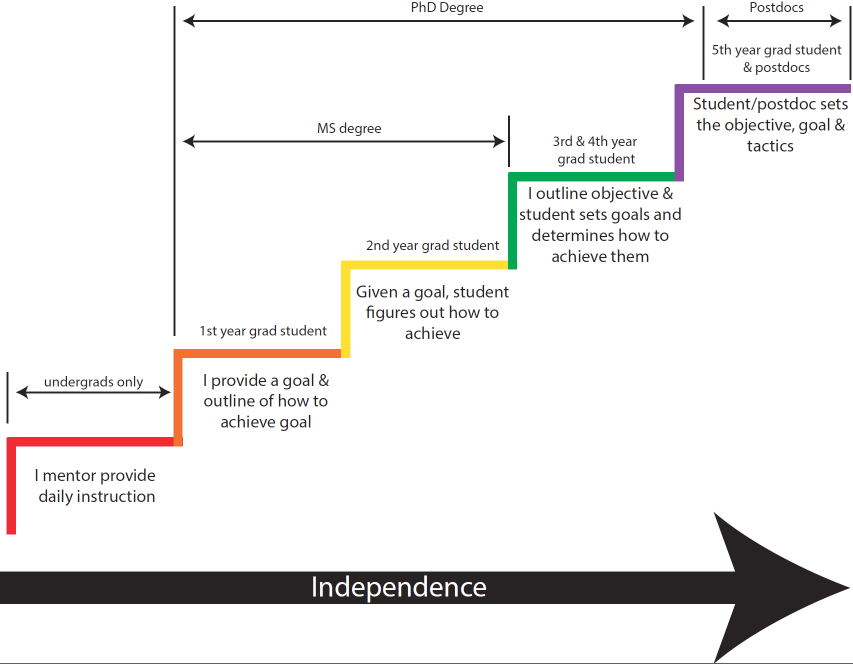

In our IDP meeting, we walk through the IDP together. We try to keep focused on bigger picture items related to: 1) our communication; 2) the mentee’s career vision and how we can help them attain their vision; 3) long-term research and career trajectories (which are often related); 4) their coursework (if the mentee is a student); and 5) the big-picture things the mentee would benefit from focusing on over the next review period. We discuss placement on our independence staircase (below, modified from Lab Dynamics) and map progress toward meeting the appropriate level of independence for the mentee. Our meetings are usually fantastic and the more reflective we (both I and the mentee) are, the more fruitful the discussion.

After the IDP, the student compiles the notes and thoughts from our joint meeting and sends to me and I file them away. Ahead of the next IDP, I revisit this file and compare the previous IDP to the current IDP to map mentee growth.

IDP Timing:

We conduct these IDPs bi-annually (January & July) so both the student and I get in the habit of reflecting on their progress in chunks that are manageable. This frequency is appropriate for new graduate students and postdocs that have short stints in our lab group. But it might be too frequent for other researchers. Given that this is an individualized process, discussing the frequency of review after a few rounds of IDPs is appropriate. For more senior researchers, annual reviews work well.

In the past, we’ve joined IDPs with performance reviews. However, we’ve recently cut this aspect out unless there are performance issues that need to be addressed. Typically, we discuss performance informally in our day-to-day conversations, so it seems a bit pedantic to do this again in a formal way. Additionally, there is something about “performance reviews” that gives folks anxiety about the whole process. IDPs are not meant to be a dissection of all the things the mentee is doing wrong or can improve on. They are a tool to improve our communication and revisit the mentees’ vision for their career and to help them grow as a scientist and as a professional.

Who do we perform IDPs with?

At first, we conducted IDPs for graduate students and postdocs only. Recently, we decided to do them at a reduced scale for undergraduates and technical staff. I felt like overlooking undergraduates was a missed opportunity to help develop junior talent.

Challenges with IDPs

We’re committed to mentoring people until they tell us they don’t want to be mentored anymore. Of course, no one makes that explicit, but it’s fairly clear when someone is not vested in the process and doesn’t put the work in to attain their own vision. A strong mentoring relationship is bidirectional and the investment we make on our end needs to be reciprocated by the mentee for this process to work.

We’ve had mentees put little effort into the IDP process. In my experience, there is usually more to the story. A lack of interest in IDPs can be a harbinger of what’s to come that culminates with the mentee leaving our group. Sometimes this is because the mentee has a better offer somewhere else. It might be that they don’t (or can’t) see progress toward their vision. Perhaps they don’t really know what their vision is. Or they are not happy with the group or my mentorship style. All of these are valid feelings. But we can’t force it. This is part of the reason we make our processes transparent and put such an emphasis on hiring (oh, and if you haven’t seen, we are recruiting doctoral students). We want to find the people that will thrive in our environment.

A second issue is that after a few IDPs, as the mentor and mentee get to know each other, there tends to be some redundancy in the discussions. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For example, this might be an indication of mentee growth and they are ready for more opportunities to be challenged in new ways. In contrast, it might also be an indication that the approaches the mentee is using to address improvement are ineffective. In this scenario, we try different approaches to accomplish the mentee’s goals with a focus on improvement, not perfection.

Finally, sometimes life punches you in the face and even the most carefully laid plans fall apart. We’ve all had life issues get in the way of progress. Family or friend illnesses or death. Relationship issues. Financial troubles. Depression. Anxiety. These have significant effects on performance and may appear to derail progress on and IDP. And these sorts of things affect everyone differently. While it’s never expected that a mentee detail a tough situation, it’s important that the mentor knows that something is going on outside of the lab so we can discuss modified expectations.

Mentees mentoring me

Finally, the benefits of this approach compound over time and make me a better mentor. Every mentee that has been a part of our group has taught me something about how to be a more effective mentor to a broader section of individuals. I’ve not always got the mentorship slice right (and I know there are a few former mentees that will agree), but it’s moving in the right direction. By regularly reviewing incremental progress and having discussions with each lab member, I have a greater appreciation for the diversity of definitions of “success” in the sciences.

Support Local Bookstores. Bookshop.org pays me a small commission if you purchase books through my links in this post.