Han Solo Bacteria

How Desert Microbes Freeze Themselves in Time

The Sonoran Desert taught me something important during the pandemic: life here doesn’t just survive dryness—it waits.

Walking with my family through the desert during those long months of lockdown, I’d watch the seemingly lifeless soil. 2020 was a particularly dry year: no rain for months. Temperatures pushing past 110°F. The ground baking under relentless sun. But I knew the soil microbes beneath our feet were doing something remarkable while waiting for water. I just wasn’t sure what.

This waiting became the question that drove our research for the next five years.

A Project That Refused to Die

Ryan Bartelme started this work in 2019, before any of us had heard of COVID-19. We had just isolated an Arthrobacter from subsurface forest soil in the Santa Catalina Mountains. The strain grew reliably, was easy to work with, and came from the kind of periodically dry soil we wanted to understand. It seemed like the perfect system to ask: What actually happens inside a soil bacterium when it dries out and then gets wet again?

The questions were straightforward. Most desiccation studies focused on rapid drying, flash-drying cells to see how they responded to sudden stress. But soil doesn’t dry overnight. We wanted to study slow drying, with proper hydrated controls so we could be certain the changes we saw were specifically due to desiccation. And while plenty of papers studied desiccation, fewer investigated rehydration: the journey back to life.

Then the pandemic hit.

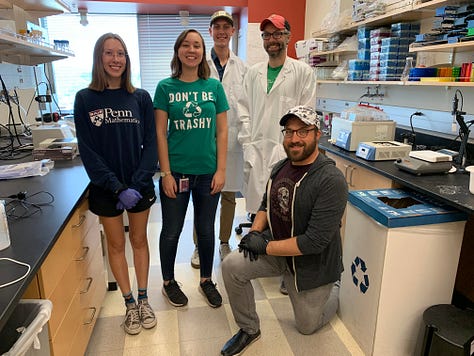

The lab shut down in March 2020. When we reopened, it was with reduced schedules, social distancing, and a rotating cast of lab members as people graduated or had their bandwidth consumed by pandemic chaos. The project survived three years of disrupted science, passed between hands like a relay baton.

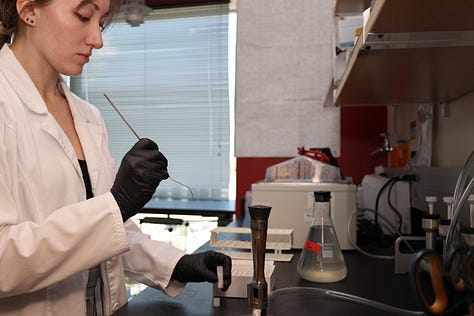

Ryan designed the humidity control system using saturated salt solutions to precisely control relative humidity. The approach was elegantly simple: different salts create predictable humidity levels, allowing us to slowly walk cells from 100% humidity down to 26% over two weeks, mimicking gradual water loss in real soil. The experimental design incorporated three essential features: hydrated controls running in parallel, slow desiccation over 14 days rather than rapid drying, and (honestly, this surprised us when it worked) rehydration with water vapor alone. No liquid water. Just shifting the dried cells back to 100% humidity and waiting.

Frozen in Carbonite

The first hint that something unusual was happening came from Izzy Viney’s Master’s work analyzing intracellular metabolites. She noticed RNA breakdown products accumulated in desiccated cells. This puzzled us. If RNA was degrading, there should be less intact RNA in dried cells.

But we could extract RNA. Not just ribosomal RNA, but messenger RNA too. Enough to sequence and analyze gene expression patterns.

This didn’t make sense. RNA is supposed to be transient. In actively growing bacteria, most mRNAs have half-lives measured in minutes. Environmental microbiologists use RNA presence as a marker of activity precisely because it turns over quickly in growing cells.

Yet here we were, extracting intact RNA from cells that had been desiccated for several weeks.

The full picture only emerged once Christina Guerrero completed the transcriptome analysis, Melanie Kridler finished the culture work and qPCRs, and Adriana Gomez-Buckley confirmed cells weren’t forming spores.

The pattern was striking. Gene expression changed dramatically as cells dried: mounting stress responses, producing protective compounds. Then, once cells were desiccated by day 8, transcription essentially froze. Between days 8 and 14, there was no significant change in RNA composition. The transcriptome was static.

The same thing happened with metabolites. Dramatic restructuring during drying. Then stasis during full desiccation. Then another wave of change upon rehydration.

Like Han Solo frozen in carbonite, the cells had pressed pause. Their molecular machinery preserved, waiting.

Water Vapor Whispers

The revelation came with rehydration. When we exposed dried cells to water vapor—just humidity, no liquid water—they woke up. Hundreds of genes increased in abundance. Energy mobilization. DNA repair. Stress response machinery.

Water vapor alone was sufficient to trigger resuscitation.

This finding excites me because it matters for real-world microbial ecology. Desert microbes don’t necessarily need liquid water to wake up. High humidity events or fog deposition might trigger resuscitation through vapor-phase rehydration. This has implications for understanding microbial activity in fog deserts like the Namib, in biological soil crusts, and anywhere vapor-phase water transfer occurs before liquid water becomes available.

What This Changes

This work challenges how we interpret molecular data from dry environments. Molecular ecologists assume RNA indicates activity. RNA:DNA ratios supposedly separate active from inactive populations. Metatranscriptomics presumably captures what communities are actively doing. But our data showed that RNA—both ribosomal and messenger—remains intact and extractable from cells that are metabolically dormant for weeks.

Soil rarely maintains constant moisture. In dryland ecosystems—covering about 30-40% of Earth’s land surface—drying is the norm. If you extract RNA from field soil, you’re inevitably capturing a mixture: some from active cells in wet microsites, some from dormant cells preserving transcripts from the last time they were hydrated.

When you grind up soil and extract RNA, you’re averaging across millions of cells in different physiological states. The transcripts you sequence might reflect what cells are doing now... or what they were doing the last time water was available. We can’t currently separate these populations.

The nucleotide breakdown products that first caught Izzy’s attention tell their own story. They accumulate during the transition to dormancy and persist through desiccation, then return to baseline upon rehydration. We think they represent internal RNA recycling. Components accumulate because there’s no new synthesis to use them. When water vapor triggers resuscitation, cells likely draw on this internal pool to rebuild RNA and restart metabolism.

A Pandemic-Era Science Story

Looking back, this paper is as much about persistence as the bacteria it studies. Ryan designing the experimental system. Izzy taking over when Ryan left, building her Master’s thesis and NSF Graduate Research Fellowship around these questions. Melanie’s patient culture work and RNA extractions. Christina’s transcriptome analysis. Adriana’s work ruling out spore formation.

The science emerged from walks in the desert during a global pandemic, from discussions about what questions actually matter, and from determination to understand not just whether bacteria survive desiccation but what they’re doing while they wait.

Soil bacteria hit pause when water disappears. They don’t just endure—they maintain themselves in a state of suspended animation, preserving their molecular machinery until conditions improve. Then water vapor whispers that things are changing, and they begin the careful work of waking up.

That’s worth understanding. Not just because it challenges how we interpret RNA in dry soils, but because it reveals something fundamental about microbial resilience in a world where drought is becoming more common. These bacteria have been waiting out dry spells for millions of years. Maybe there’s something we can learn from their patience.

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like our previous “behind the paper” stories about relic DNA in soil, compact microplate readers, and genome evolution in deep-sea bacteria.